Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Eastland Disaster, the largest loss of life from a single shipwreck on the Great Lakes. Western Electric employees, families, and friends were to cross Lake Michigan from Chicago to Michigan City, Indiana, for a picnic. But the SS Eastland, docked at the Clark Street Bridge, never left the Chicago River. The ship rolled over into the river only 20 feet from the wharf’s edge. More than 2,500 passengers and crew members were on board that day. Hundreds were trapped inside because of the sudden rollover; others crushed by heavy furniture. Ultimately 844 people lost their lives, including 22 entire families.

More passengers were killed on the Eastland than the Titanic and the Lusitania, which was torpedoed a few months before. Many of the Eastland victims were Czech immigrants, which might explain why the event has largely been forgotten. Ted Wachholz, president of the Eastland Disaster Historical Society, has a theory on why the Eastland looms so much smaller in American history: “There wasn’t anyone rich or famous on board. It was all hardworking, salt-of-the-earth immigrant families.”

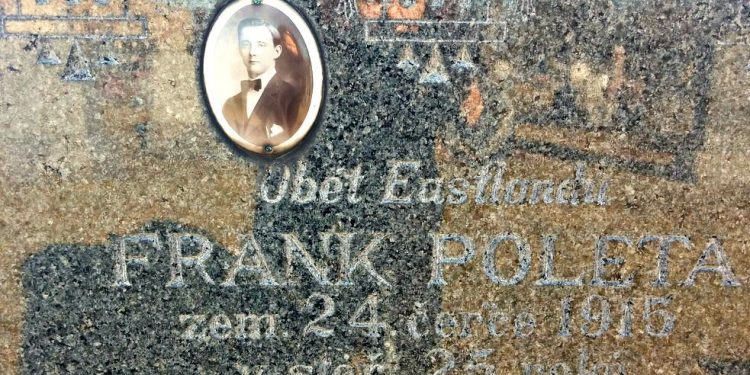

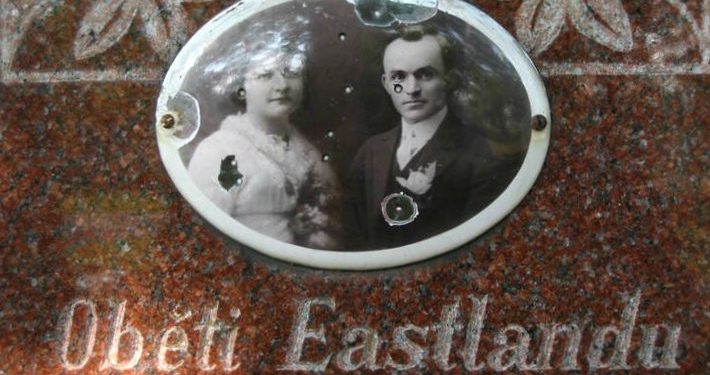

Chicago’s Bohemian National Cemetery, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is the final resting place of the largest number of victims, 143 to be exact, most found in Section 16. The cemetery is made more interesting by the fact that numerous graves are covered in photo ceramics, making the names on the headstone come “alive”. You find yourself asking questions like “Who was this person?” and “What were their interests?” and “What could they have done if they lived?” You can see the faces of Eastland victims Ruzena M. Henzlik and Frank Poleta, both so young, which was true of many of the victims who died that day. Then there is Western Electric employee Julius Schroll who perished alongside his wife, Emma, and her two sisters, Anna and Pauline. There is also a glass-fronted columbarium, a building used to store funeral urns, that is full of niches displaying more photo ceramics and personal mementoes of the deceased. And just last week a new memorial was unveiled in a half hour ceremony for the “Eastland Centennial Commemorative Project,” which was attended by descendants of both survivors and victims of the event. It’s best not to look at the cemetery as a creepy place, but a funerary museum of art and history dedicated to keeping memories alive for the next generation.