When it comes to house museums, there will always be the Gilded Age mansions of Newport, like The Breakers, or a place where Abraham Lincoln once slept, like the Soldiers’ Home, but what about the buildings not connected with the rich and famous? What about the houses that should be preserved solely for their architectural value? Architecture is a form of art, you can’t just pick up a building and place it next to the paintings and statues displayed in the local art museum. It doesn’t work that way. Even though there are many examples of putting bits and pieces of a building into a museum, like the Frank Lloyd Wright Living Room in the Met, a structure is meant to be experienced as it was originally created, and that’s where the house museum comes in. If a buyer cannot be found for a one-of-a kind design, what is the best choice: would you let it be demolished, or instead let it be preserved and shared with the public? Of course preservation is always the right thing to do, but sometimes it’s a difficult battle to win.

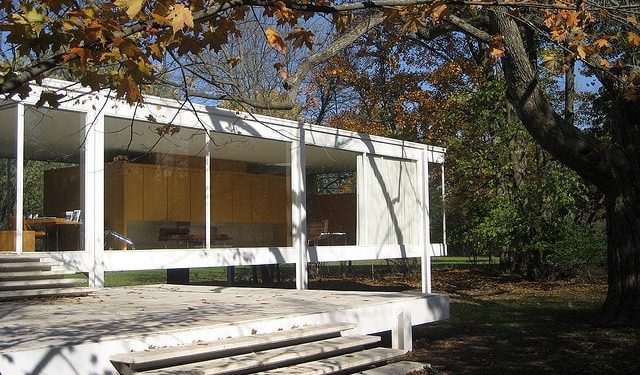

Not long after it was saved and opened to the public, I visited Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois. I am not going to write endlessly about my personal experience (wearing special booties in a minimalist glass house is…strange) or whether or not Miesian architecture is my cup of tea (it really isn’t…but I appreciate it more than I did) because that’s not the point of this post. It’s about how one of the most significant designs of the 20th century, a world-famous building by a world-famous architect, was not turned into a house museum as easily as you thought it would be. When the building was put up for auction in 2001, with the possibility of it being moved into a rich man’s private art collection, architects and preservationists took action. In order to protect the house, the State of Illinois had to buy it. Many buildings are integrated with nature, and the Farnsworth House is no exception with its landscape of meadows and trees situated along the Fox River. It would be a tragedy for the house to be moved. Worse yet – the 58 acres could be subdivided and developed. Even with a strategy formed in preserving the landmark with support from then Governor George Ryan, the Attorney General nixed the plan, which is ridiculous when you think about all the “pork” and favors that occur when it comes to government spending.

With a grassroots approach, preservationists grouped together to find as much support as they could. The Landmarks Preservation Council pledged a million, along with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. They were short $3.6 million 24 hours before the auction, but momentum quickly built. An NPR piece helped boost pledges. A last-minute fund-raising effort raised the 7 million dollars needed to outbid any rivals at the auction. Everything turned out right in the end, but why did it have to be such a nail biter? I know the government can only do so much, but other countries recognize the need to conserve and support their cultural heritage for the good of the public. Why does America have such a difficult time getting this right? The built environment is just as important as anything else associated with public history. Of course George Washington’s house should be preserved, but so should a Farnsworth House or an untouched 18th century Georgian-Palladian House, no questions asked. The fact that preservationists were able to get enough public donations to save Farnsworth proves there is a ready and willing audience. And from my experiences working at historic house museums, I have been exposed to tourists from all over the world who are more than happy to pay lots of money and go to the middle of nowhere (and Plano, Illinois certainly is nowhere!) to see buildings like the Farnsworth House.